Ascites isn’t a very common condition in backyard chickens. That is not to say you won’t come across it if you keep poultry. Ascites is not an actual illness in itself. Rather, it’s a symptom of an underlying condition pointing to the fact that there’s something terribly wrong with your chicken.

What exactly is ascites, and what causes it? Here’s everything you need to know about the condition.

What Is Ascites

Ascites aka water belly is a condition brought about by fluid buildup in a chicken’s peritoneal cavities. This buildup results from heart failure or pulmonary hypertension and is more common in aging hens and broilers.

What Causes Ascites (a.k.a. ‘Water Belly’)

Broilers have an abnormally fast growth rate. Their immature heart and lungs are simply unable to keep up with the increasing demand for oxygen, and the heart responds by increasing blood flow into the lungs. The chicken’s rigid lungs are, in turn, unable to handle the increase in pressure brought about by the spike in pressure. As a result, the heart works even harder to keep the blood flowing throughout the body.

Eventually, the increased demand on the heart causes it to enlarge, and its walls thicken to the point the right valve is no longer able to close. Blood then backs up into the liver, causing fluid in the organ to leak out into the body cavity, hence the – water belly in chickens.

In aging hens, the condition comes about the same way, except in this case, the contributing factors could be a combination of obesity, poor ventilation, genetic predisposition, internal laying, tumors, infections, fungi, and other toxic elements. Poultry flocks in higher altitudes are also more susceptible to ascites.

Symptoms

The symptoms of ascites in birds are oftentimes similar to those of egg-bound chickens. However, rather than the penguin-like posture observed in egg-bound hens, chickens with Water Belly adopt a wider-legged stance due to their fluid-filled cavities. If you reach down and feel their abdomen, it feels soft and squishy, unlike that of an egg-bound chicken which feels firm.

Ascites is not contagious, meaning it cannot be transmitted among your flock. The underlying cause of the condition is heart disease. When the chicken’s health has deteriorated to the point ascites is present, the situation is too far gone. It is not curable, and it cannot be reversed.

Treatment

Although there is no way to cure ascites, there are some measures you can take to prolong their life and also ease their discomfort. It’s important to mention at this point that before you attempt to perform this procedure yourself, it’s a good idea to have a veterinarian look at it first, especially if you have no prior experience treating water belly in chickens.

With that in mind, the most common and effective way to relieve the discomfort caused by the condition is to drain the fluid from your chicken’s abdominal cavity. As scary as this might sound, it is a fairly straightforward procedure if you have the right equipment at hand.

How to Drain a Chicken With Ascites

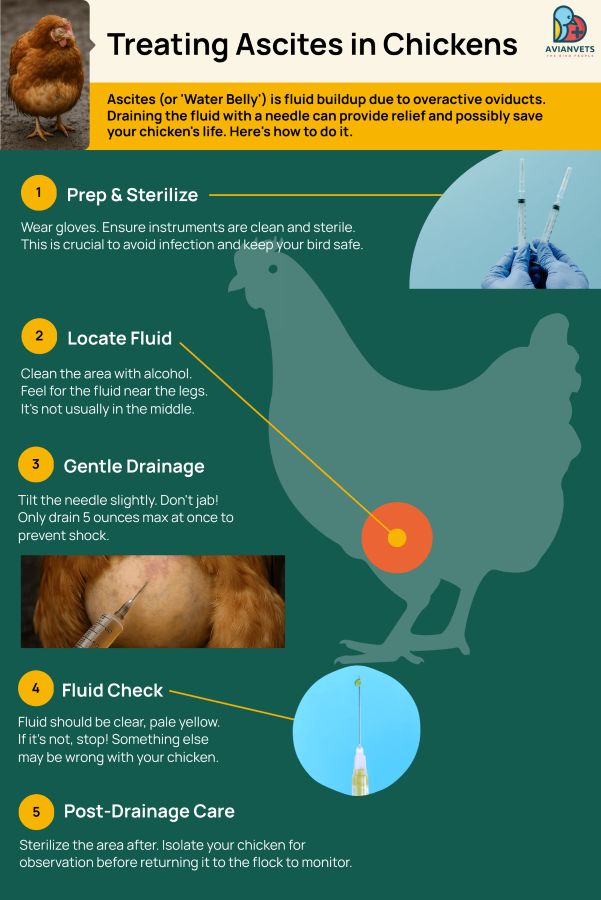

Below is a step-by-step guide on how to do the procedure.

- Put on disposable gloves and ensure that the instruments and equipment you’ll use for the procedure are clean and sterile.

- Use a sterile needle, syringe, or catheter for the procedure. It should be large enough to drain or draw the fluid all the way through.

- Using isopropyl alcohol, clean the chicken’s abdominal area on the right-side-down, moving toward the vent area.

- Feel around the abdomen to identify the exact location of the fluid. It will usually be close to the legs as opposed to the middle part of their body.

- Holding the chicken securely with one hand, carefully insert the needle, syringe, or catheter into the abdomen. Ensure you tilt it at a slight angle at the point you feel the presence of fluid.

- Gently push the needle into the peritoneal cavity. Don’t jab it straight in, as you might end up injuring the neighboring organs.

- Once the needle is in the fluid, draw off no more than five ounces of fluid. Drawing off too much at a go will send the chicken into shock.

- If your syringe’s capacity isn’t big enough to hold all the liquid, carefully remove it from the inserted needle and allow the fluid to drain on its own into a container. This will allow you to track how much of it is draining.

- The color of the draining fluid should be clear with a pale yellow tint. If the liquid in question is any color other than this, you should stop immediately. Your chicken could be suffering from a condition that is not ascites.

- Once you’re through, wipe down the area with alcohol to sterilize it. You don’t want the area to get infected. Keep your chicken isolated from the rest of the flock so you can observe her before releasing her to the coop.

How Often Can Ascites Be Drained?

Depending on the severity of the chicken’s condition, you’ll probably need to repeat this process every couple of days or weeks. Remember, this procedure is supposed to ease their discomfort and is not in any way a cure for their condition.

How Long Can a Chicken Live With Ascites?

Ascites does not have a cure, and the prognosis is poor. The duration a chicken can live with Water Belly comes down to the bird’s condition and whether or not it receives the treatment outlined in the section above.

If the underlying condition is not remedied, some birds deteriorate quite fast, and most end up dying within a week or two. Those that end up getting the fluid drained can survive a few months but their condition will gradually deteriorate.

Final Thoughts: Caring for a Chicken With Ascites

While ascites—or “water belly”—may not be one of the most common conditions in backyard chickens, it’s one of the most distressing to witness. That’s because ascites isn’t a disease in and of itself. It’s a serious symptom of deeper health issues like heart failure, internal organ stress, or metabolic dysfunction. By the time fluid buildup is noticeable, the condition is often too advanced to reverse.

Still, compassionate care matters. Regular draining can bring meaningful relief to a hen that’s otherwise bright, eating, and moving around. While there is no cure, your effort to manage her comfort speaks volumes about the kind of attentive poultry keeper you are.

If you notice signs of labored breathing, swelling in the belly, or a penguin-like stance in one of your hens, don’t assume she’s just egg-bound. Always check for ascites—and if you’re unsure, consult an avian veterinarian before attempting treatment.

Above all, focus on prevention: support your flock with good nutrition, proper ventilation, low-stress environments, and regular health checks. These small practices go a long way in reducing the risks of heart-related complications, especially in fast-growing breeds or aging layers.

If you suspect ascites in your flock and feel unsure how to proceed, don’t hesitate to reach out to a vet who specializes in poultry. Your quick action and care might not cure the condition—but it could give your bird more time, more comfort, and a better quality of life.

In the meantime, are you thinking of getting a caique as a pet? Before you do, you might want to check out our blog first.